Drought conditions across much of Kansas could cost wheat farmers more than $1 billion

As drought deprives western and central Kansas of rain, farmers are bracing for a drop in production that threatens to barely cover input costs.

Crop experts project yield to drop by more than 100 million bushels from last year's harvest, worth more than $1 billion at current commodity prices.

In the Wheat State, sometimes called the breadbasket of the world, the hit to crop yields will hurt exports at a time when the Russian war in Ukraine threatens the global food supply.

"That is driven primarily from severe drought, particularly in the southwest part of the state, and to a certain degree in the south-central part of the state," said Ernie Minton, dean of Kansas State University's College of Agriculture.

Recent rainfalls at the end of May offer little hope for parched ground.

"I think I saw standing water for the first time on the ground in like eight or nine months here," said Clay Schemm, a farmer near the western Kansas town of Sharon Springs.

While the rain is needed, it won't make a difference for many fields across the state.

"When you get extreme drought late in the season, you can have a really shriveled wheat berry," Schemm said. "This is going to help finish filling it out, but as far as doing any serious benefits for the wheat crop, it's too little too late."

More: Republican group files ethics complaint after Laura Kelly's campaign challenged ad

Drought emergency and little rain

Western Kansas is dryer than normal, according to National Weather Service data through April.

In Dodge City, the 2.27 inches of rain over the first four months of the year is the second-worst precipitation mark since 2006. In Goodland, the 1.93 inches is the second-worst since 2002. Goodland has had 2.25 inches of total precipitation between October and April. The average for that timespan is 5.93 inches.

Winter wheat is typically planted in September and October, then harvested in June and July.

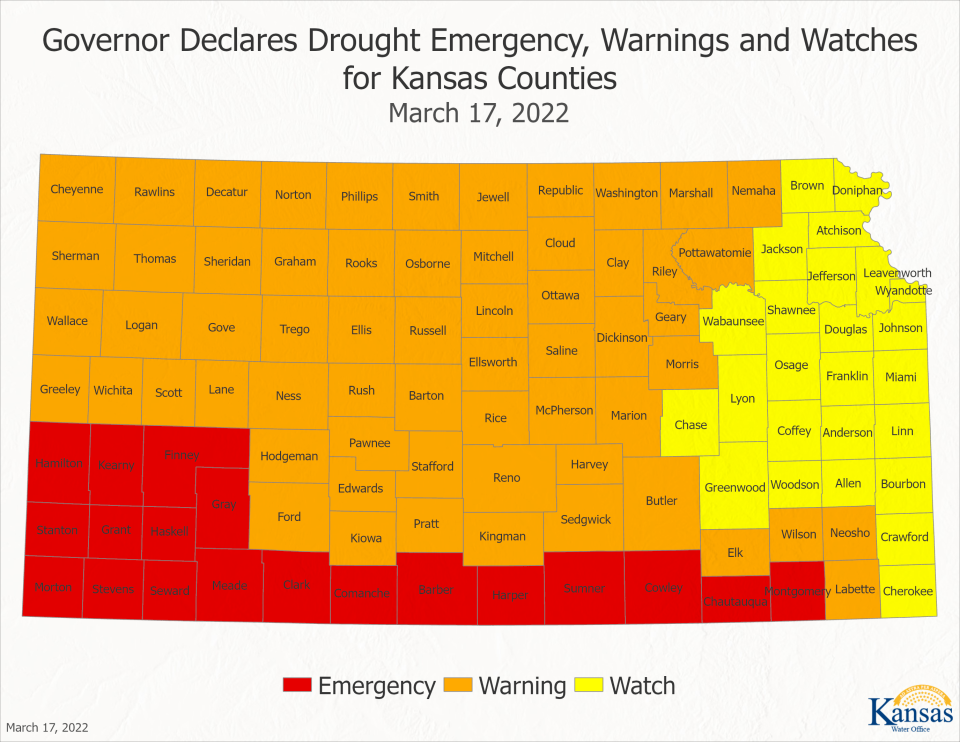

In March, Gov. Laura Kelly issued a drought emergency declaration for all 105 counties, with 25 in a watch status, 61 in a warning and 19 in emergency status.

"It is part of the variability that we see in Kansas wheat production," said agronomy professor Romulo Lollato, who is also a wheat specialist for K-State Research and Extension. "But again, it's unfortunate that we're seeing on the low end this year again, just because we put so much into that crop. It's out there nine months out of the year, the growers doing so much to try and keep that crop growing."

Kansas farmers have turned to such conservation practices as no-till farming, which helps conserve moisture and reduce the amount of dust blowing away in the wind, said Marsha Boswell, a spokesperson for the Kansas Wheat Commission and the Kansas Association of Wheat Growers.

"They want the land to be in a better place than when they acquired it," Boswell said. "They are doing farming practices that are beneficial to the land, and hopefully do things that maintain the moisture they do receive. So, you know, 100 years ago, if we went this long without any moisture on that, we wouldn't be able to really produce a crop at all."

Farmers also have improved varieties that are more tolerant of drought and heat.

"We can do better genetics. We can do better agronomy," Lollato said. "But if Mother Nature doesn't cooperate, in the end, that's the biggest driver."

More: Amid drug and immigration concerns, Roger Marshall and five Kansas sheriffs visit border

Wheat tour projects drop in yield

The Wheat Quality Council conducted its 2022 hard winter wheat tour across Kansas in mid-May.

Lollato said the tour's purpose is to estimate crop yield while connecting people from agricultural industries, many of whom have never before seen a wheat plant.

The tour provides those related industries — such as flour millers, bread bakers, bankers and grain commodity traders — with an idea of the quality and quantity of production they can expect. The experts base their calculations on more than 500 field estimates, plus some gut feelings.

Fields in the northeast part of the state were in good shape, Lollato said, but "it got bad in a hurry" as they headed into north-central Kansas and farther west. In northwest Kansas, they found drought-stressed fields with short crops that are unlikely to yield more than 15 bushels an acre.

"As we moved to southwest Kansas, it seemed like the conditions deteriorated even further," he said. Once they moved to south-central Kansas, Lollato was surprised that "those dry conditions extended much farther east that what I would have anticipated."

Heat stress, via the early May daytime temperatures surging past 90 degrees, further hampered production. The more recent cooler temperatures and moisture will "help the crop maintain whatever yield potential it has — which is low," he said.

Some northern areas of the state will see more benefit from late spring rainfall because their fields are behind in the crop cycle.

Thunderstorms also bring a threat, however: Hail.

"We call it the great white combine," said Schemm, the western Kansas farmer.

His best-looking field had enough snow and rain over the winter and spring that it'll do OK, even though its yield will be about 10 fewer bushels an acre than normal. His fields typically average around 40-45 bushels.

One of his rougher-looking fields is seven miles to the south and missed on the spotty storm cloud lottery.

"It might make 10 (bushels an acre) if we're lucky," he said.

More: Laura Kelly signs Kansas budget funds schools, but calls for more special ed money

Lost production worth $1 billion

This year's tour predicts a substantial drop in production, despite farmers planting more acreage than last year.

Kansas Wheat reported that the tour projects 261 million bushels of wheat to be harvested in Kansas this summer after planting an estimated 7.4 million acres in the fall. The industry expects 39.7 bushels per acre, coupled with a higher-than-normal abandonment rate of 11%.

U.S. Department of Agriculture data showed 7 million acres of wheat were harvested in Kansas last year after 7.3 million acres were planted.

At an average yield of 52 bushels an acre, the state produced 364 million bushels in 2021, according to the USDA's National Agricultural Statistics Service. At a price of $6.55 per bushel, the value of the production was nearly $2.4 billion.

That year, Kansas farmers produced the most wheat of any U.S. state.

Now, a projected drop in yield of 103 million bushels from last year's figure, at $12 a bushel for hard red winter wheat, would be more than $1.2 billion in lost production.

"We won't know until that grain is in the bin exactly what it looked like and how it produced," Boswell said.

Rural Kansas economies may suffer from drought

The lost production hurts local communities and rural economies.

"People don't necessarily like to talk about it, but the easiest place to see it is usually at the county fair," Schemm said. "County fair in my area is a pretty big opportunity for people to give back to the kids. ... And on a year like this, everybody's belts are cinched a bit tighter."

There also tends to be less activity around town, and the events that do happen are scaled back. The smallest towns may see the biggest struggles.

"If you've got one or two big guys in the area, and they're having a really rough year, that community can be pretty dry as far as activities going on or trying to keep that community alive and keep people around," Schemm said.

Other businesses are also affected when the farm budget margins are slim.

"I know a few of the business owners in our community, and each year that we have a tough year, they start getting prepared for a tight year as well," Schemm said. "Because farmers in the community, so much cashflow passes through them from grain sales, and they distribute a lot of that money back into the community.

"It's hard to distribute a pool of money when there's just not near as much money there."

More: Laura Kelly will sign gradual food sales tax cut plan from Republicans, wants it implemented sooner

High wheat prices may not be enough to cover input costs

After peaking at $13.79 a bushel in mid-May, hard red winter wheat futures closed the month at $11.65. Wheat prices were in the low $8 range in February, but spiked after Russia invaded Ukraine.

The May wheat outlook from the USDA's Economic Research Service projects a record-high season-average farm price of $10.75 per bushel this coming year, up $3.05 from the previous year.

"It's not just a cash cow for farmers with this high wheat price," Schemm said. "With the year that we've had, supply chain disruptions and increased input costs, it's kind of allowing farmers to stay afloat."

Despite the high commodity prices, many farmers must make an economical decision of whether to harvest a low-yielding field.

"We've got this interesting confluence of very, very high commodity prices, with farmers deciding whether to abandon the crop," said Minton, of K-State's agriculture colleg. "For now, maybe with $13 wheat, it's worth going ahead and harvesting. That's where some of the real uncertainty going into the last few weeks prior to harvest that are going to play out."

#wheat area abandonment due to drought in SW KS. #wheattour22 @KansasWheat @KStateAgron https://t.co/mw31IBd4LW

— Romulo Lollato (@KSUWheat) May 22, 2022

While there are costs to operating combines and running trucks, at the current market price, "It's not going to take a whole lot of wheat to break even," Lollato said.

Still, the higher commodity prices might not compensate for the drop in production combined with rising input costs, Boswell said. While crop insurance may be available, it more "compensates them for some of those expenses that they've already had, giving them the opportunity to put another crop in the ground next year."

On Schemm's farm, they typically work the ground or spray it before the seeds are planted. The tractor burns about 12 gallons while covering about 35 acres an hour.

"You do that three times, you're burning essentially a gallon per acre," he said. "So there's an extra dollar per acre, bare minimum, when you start increasing the cost of diesel fuel as you start running across it, and it's not even including getting the crop in the ground."

During harvest, Schemm's 500-gallon fuel tank will be used in a day and a half.

High fertilizer costs, which are by natural gas price spikes and Russian gas embargoes, may be contributing to some of the drop in production.

More: Kansas lawmakers want Joe Biden to ban Russian oil. The president already did.

Wheat farmers typically use 70-80 pounds of nitrogen fertilizer per acre during the spring green up, Lollato said.

"I have heard of a few growers here and there this year who did not fertilize ... because of a combination of high price and low yield potential," he said.

Two years ago, Schemm could buy nitrogen at about 60 cents per unit. Last year, it was up to $1.07.

Weed-killer prices have also increased. Schemm bought his Roundup last year at $9.95 a gallon, and he uses about a quarter of a gallon per acre each time he goes across the field. As of March, the herbicide cost $50 a gallon, he said.

"As much as seeing the price can be nice, I think a lot of people forget about all of that backside investment," Schemm said. "Because even right now, the logistics of putting wheat in the ground or harvesting wheat can get very hard."

Schemm said his operation can make a profit today off $12 wheat, but if input costs keep rising, his farm would likely take a loss next year at the same price.

"How do you balance that with trying to make sure you keep getting the crops in the ground and keep feeding people?" he said.

Kansas exports can't compensate for Ukraine

"Typically, half of the wheat in Kansas is exported," Boswell said. "But since we're down so much, we're not going to be able to export as much and bring in that export money into the economy."

Russia was the world's top wheat exporter last year, and Ukraine was No. 5, according to USDA data.

"There's just not as much wheat available on the world market," Boswell said. "We don't really have necessarily a supply issue in the United States because we will be able to use that wheat domestically."

While they might not go hungry, American consumers will be paying more at the grocery store and at restaurants.

The Consumer Price Index reflects inflation in agricultural commodities. Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation data show cereal and bakery product prices rose 10.3% from April 2021 to April 2022. Food in general saw 9.4% inflation year-over-year.

Despite worse wheat production in Kansas and many other states, some northern and northwestern states are projecting increased yields, USDA data show. Still, 68% of winter wheat production nationwide is in areas experiencing drought, compared to 34% a year ago.

American wheat exports for 2022-23 are projected to be the lowest since 1971-72.

"In the U.S., we'll be able to get our wheat," Schemm said. "But you start to get really concerned about countries that rely 100% on imports, especially from Ukraine."

The United Nations has warned that a global food crisis could lead to famine.

"When war is waged, people go hungry," said U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres.

Jason Tidd is a statehouse reporter for the Topeka Capital-Journal. He can be reached by email at jtidd@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter @Jason_Tidd.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Kansas wheat farmers could lose $1 billion due to drought conditions